Grain Boundary Migration in Metals

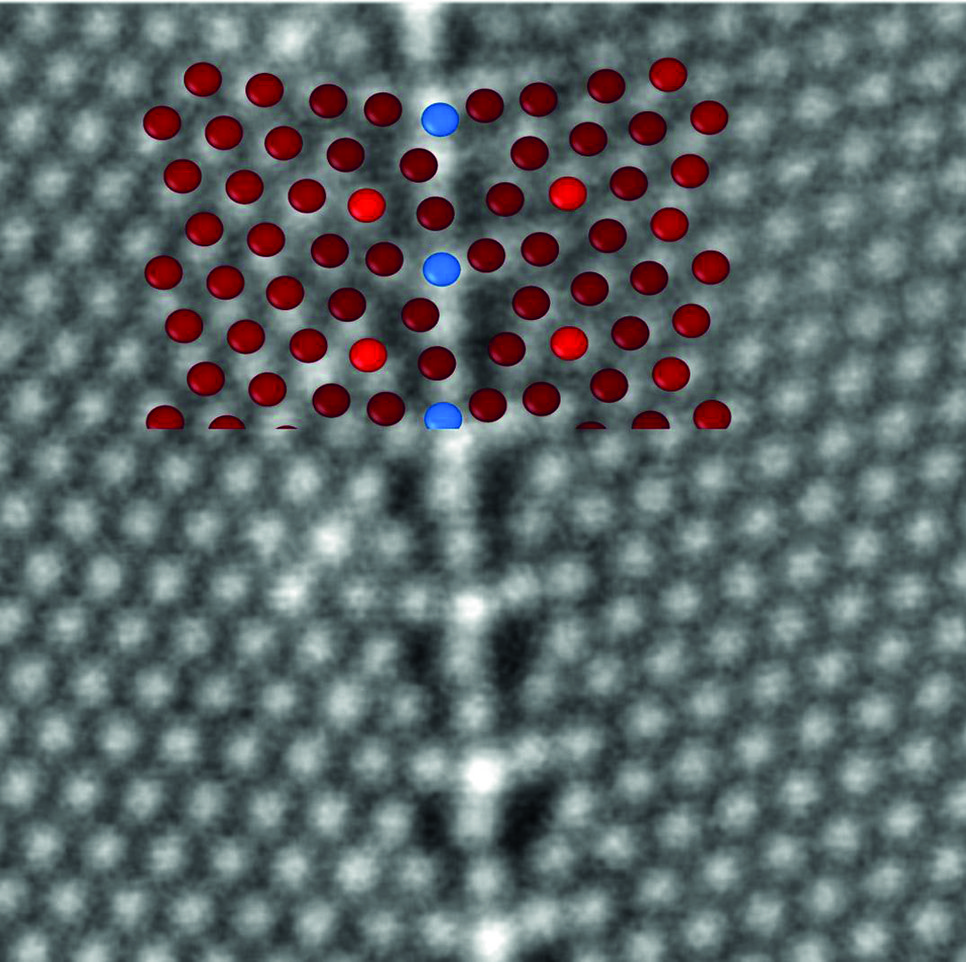

Fig. 1: A TEM observation of the Σ7 Al grain boundary studied in the grain boundary migration experiments. The overlapping simulation results show that the binding energy of copper atoms to the Al grain boundary is strong at the blue sites in perfect agreement with the experimentally observed segregation.

In a recent work [1] we, the group “Adaptive Structural Materials” in the department “Computational Materials Design”, studied the kinetics of general grain boundary migration using classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. Because the time scale of MD simulations is orders of magnitude smaller than in the relevant experiments on migration, we used a multi-scale approach to predict grain boundary migration at experimentally relevant time scales. Having identified the atomistic mechanisms of motion, we developed mesoscale models and extrapolated the migration energy barrier to small, experimentally applied forces. The asymptotic behaviour of these models in the zero driving force limit can now be compared to experimental results. Note that theoretically flat (symmetric) grain boundaries are immobile at low driving forces. The studied non-symmetric and general grain boundaries have energy barriers that are a few factors up to an order of magnitude smaller than the experimental ones derived from our collaborators at the RWTH Aachen University [2]. This gap can be attributed to impurities segregating at grain boundaries.

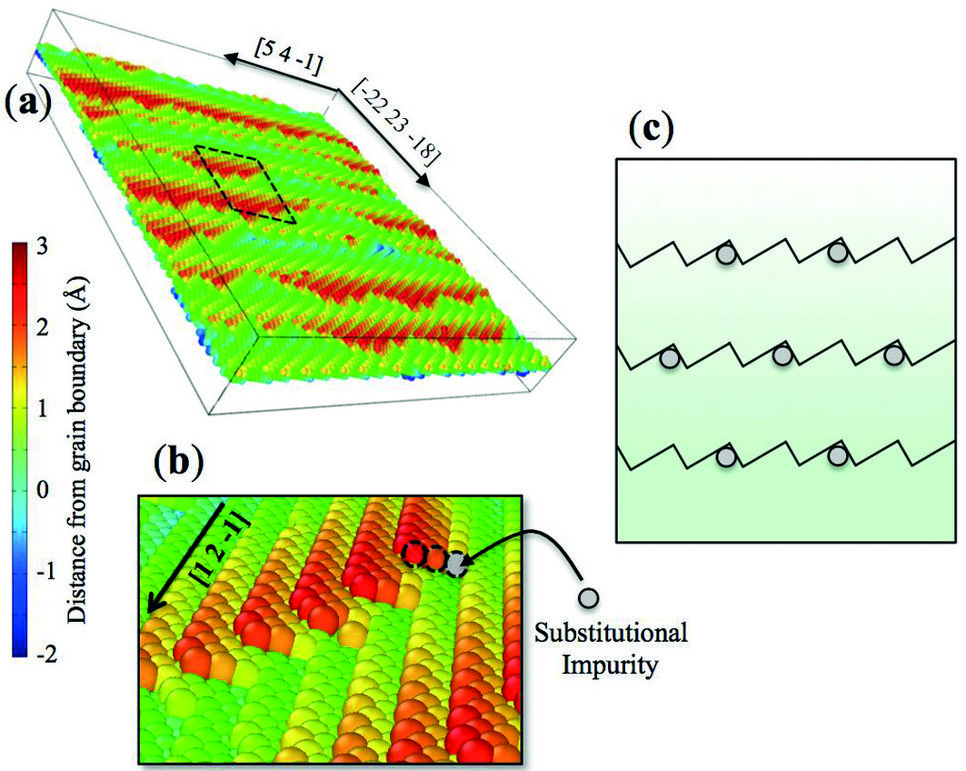

Fig. 2: This figure shows the general structure of a moving grain boundary. The kink sites serve as the positions for the substitutional impurities (a and b). A 2D kinetic Monte Carlo model as schematically shown in (c) will be used to simulate the migration in the presence of impurities at experimental time scales.

To investigate this gap in migration barriers we produced transmission electron microscopy (TEM) samples from the experimental bi-crystals that were used to study grain boundary migration. Fig. 1 depicts the atomic structure of a Σ7 boundary captured by high resolution TEM measurements performed by the department “structure and Nano-/Micromechanics of Materials” at the MPIE. Even though the purity of the macroscopic Al samples has been reported to be about 5 ppm, the grain boundary structure has been fully decorated with Cu atoms. We use this observation as corroborative evidence that impurities can always be existent in experimental settings, thus affecting the results.

To further investigate the role of impurities in migration, we are currently utilizing our knowledge about the kinked migration of a general grain boundary (see Fig. 2a and b) to place substitutional impurities at the kink sites (those have the highest binding energies), to run MD simulations and to design 2D kinetic Monte Carlo simulations with the geometries such as the one shown in Fig. 2c. We expect higher energy barriers due to changes in atomic shuffling mechanism at the kink sites caused by the impurity atoms.

References:

Authors: R. Hadian, B. Grabowski